DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC ON EMPLOYEE ADAPTATION TO UNCERTAINTY

TAMING UNCERTAINTY: A FACTOR IN PERFORMANCE AND WELL-BEING AT WORK

In a world where complexity has increased by a factor of x35¹ over the past 50 years, adaptability seems more than ever a key element to consider in combining performance and well-being. Indeed, we observe that people who know how to adapt to a changing and uncertain environment have a high level of curiosity (correlation at 0,59²), have a high capacity for innovation (0.57²) and are highly committed to their work ( 0,59)². They actively contribute to the transformation of their organization, enabling it to achieve its business objectives.

A high level of adaptation to uncertainty also has a positive effect on well-being and motivation. Indeed, employees who are tolerant of uncertainty are better able to regulate their emotions (0,65²)are more proactive in the face of stress (0,54²) and feel happier (0,53²).

And yes, managing uncertainty is a fundamental concept that interacts with a wide range of human skills, involving emotional, cognitive and social competencies.

The latest theories in cognitive neuroscience make the brain’s ability to adapt to uncertainty one of the fundamental dimensions of its functioning.

Indeed, the theory of the PREDICTIVE BRAIN³ explains that anticipating future events is one of the brain’s basic functions. We spend a great deal of time (48%) of our time rambling, automatically generating scenarios for the future. Once generated, some people will accept that a negative scenario has a small probability of happening, while other individuals will not tolerate the possibility of a negative outlook, even if its probability is infinitesimal. This is what differentiates people who are tolerant and intolerant of uncertainty. This dimension impacts on many others directly linked to performance and well-being.

ADAPTING TO UNCERTAINTY: WHAT DOES THE COMPANY KNOW?

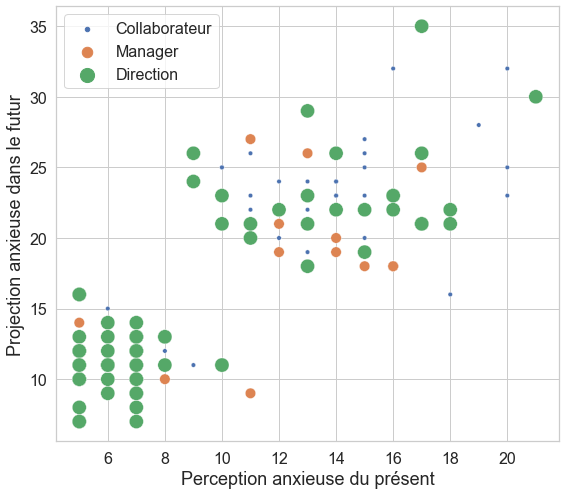

Our data show that the higher up the hierarchy you go, the more tolerant you are of uncertainty. Indeed, the perception of uncertainty, measured by anxious perception of the present and anxious projection into the future, is often more mature at management level. But this is not always the case!

We need to know who will naturally take on the role of pilot and relay in an uncertain world.

HOW NEUROSCIENCE CAN MAKE YOUR ORGANIZATION RESILIENT IN THE FACE OF UNCERTAINTY?

3 CONCRETE ACTIONS TO TAKE NOW

Discover the infographic ⬇

Bonus: a few best practices to adopt

- USE A MENTAL SIMULATION TECHNIQUE: ask your employees to imagine what they would do in a challenging situation. The aim: get them to visualize a plan from different perspectives and in different contexts, with a view to improving their ability to change to an alternative plan when the environment encourages it.

- IDENTIFY THE “ANXIOUS” AND AUTOMATIC THOUGHTS that make them anticipate the future as problematic. Once they’ve recognized that this is just a thought and not something real, they can give it a rational probability of occurring in the future, which will often be much lower than their first a priori.

- WORKING ON NEGATIVITY BIAS: human beings have a propensity to pay attention to negative information. Become aware of this and build a positive belief towards the future by embracing uncertainty. One of the best ways to counter the negativity bias is to keep a gratitude journal⁴.

At Omindwe are developing new experiences in human skills training, based on neuroscience and technology. Our aim? To engage learners differently, so that they themselves become aware of what they need to change.

¹ Morieux, Y. (2012). Smart simplicity. Own the Future: 50 Ways to Win from the Boston Consulting Group, 335-341.

² Correlation coefficients between motivation and the other variables in the model. A correlation coefficient of >0.5 is interpreted in particular as a strong correlation.

³ Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nature reviews neuroscience, 11(2), 127-138.

Andy Clark | Hacking the Predictive Mind

⁴ Duckworth, Steen and Seligman, (2005). Positive Psychology in Clinical Practice, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1(1):629-51.