HOW CAN NEUROSCIENCE HELP YOUR LEADERS MAKE THE RIGHT DECISIONS?

1) No, decision-making is not "rational"!

- SYSTEM 1 is fast, automatic and relies on biases or “mental shortcuts” to make decisions;

- SYSTEM 2 on the other hand, is slower, more deliberate and more analytical.

2) Making the "right" decision: a question of balance

So whether our emotions intervene for better or worse in decision-making, researchers agree on one thing: we need to aim for a balance between emotional signals and cognitive analysis⁴. In other words:

-

- OR TOO LITTLE EMOTION: So, if there are lesions in brain regions involved in emotional processing, researchers have shown that we can’t properly assess gains and risks – and that’s even if cognitive abilities are intact.

- OR TOO MUCH EMOTION: When we are overwhelmed by emotion, automatic mode and our biases take over our reasoning abilities. Daniel Kahneman has highlighted the cognitive bias of loss aversion: humans tend to consider a loss more important than a gain, on the order of 2.5 x more. In the context of economic decision-making, this translates into less risk-taking for fear of losing one’s investment. This discovery earned Kahneman the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002.

We might as well face up to the fact that major decisions, whether in the private sphere or at work, are the result of both our emotions and our cognition. It’s up to us to find the right dose in each case!

3) We have the power! Taking a step back and becoming self-aware

NeuroConseil #1: Cultivate your meta position

According to Houdé ⁵-⁶the brain is equipped with an INHIBITORY CONTROL SYSTEM which helps individuals to overcome automatic responses and focus on relevant information. This inhibitory control system is particularly important for high-level cognitive processes, such as PROBLEM-SOLVING AND DECISION-MAKING.

Clearly, by being more aware of our biases, and more conscious of our emotions, we have the power to balance emotion and cognition when making decisions. It’s even a region of the prefrontal cortex that develops, as can be seen on brain imaging!

When you have to make an important decision, take a 5-minute break and put your paintings aside. Excel and ask yourself: what’s influencing my decision? What am I afraid of losing?

NeuroConseil #2: Decide as a team, and adopt the right method!

Making decisions as a team helps to develop perspective and reduce bias. At least if certain conditions are met.

The researchers tested various hypotheses about what makes for good team decision-making⁷and show that the best decisions are made when sharing is MAXIMIZES SHARING within the group: sharing expertise, positive as well as negative feedback, or even responsibilities.

Need to decide on an investment, a major team change, or the launch of a new product line? Then follow the 5 golden rules of shared team decision-making:

EXPERTISE

Ask at least 2 experts to conduct the analysis in parallel, to get a more complete picture of the problem and potential solutions.

CHALLENGE

Explicitly allow everyone to question expert assumptions and biases, reducing the risk of error

BALANCE

Share workloads and responsibilities to reduce pressure on individual decision-makers

POSITIVE

Engage everyone in providing emotional support and positive feedback, improving group morale and motivation and reducing the risk of groupthink

FEEDBACK

Quickly review the decision-making process to improve the team’s overall performance.

NeuroConseil #3: Embrace your talents through play and neuroscience

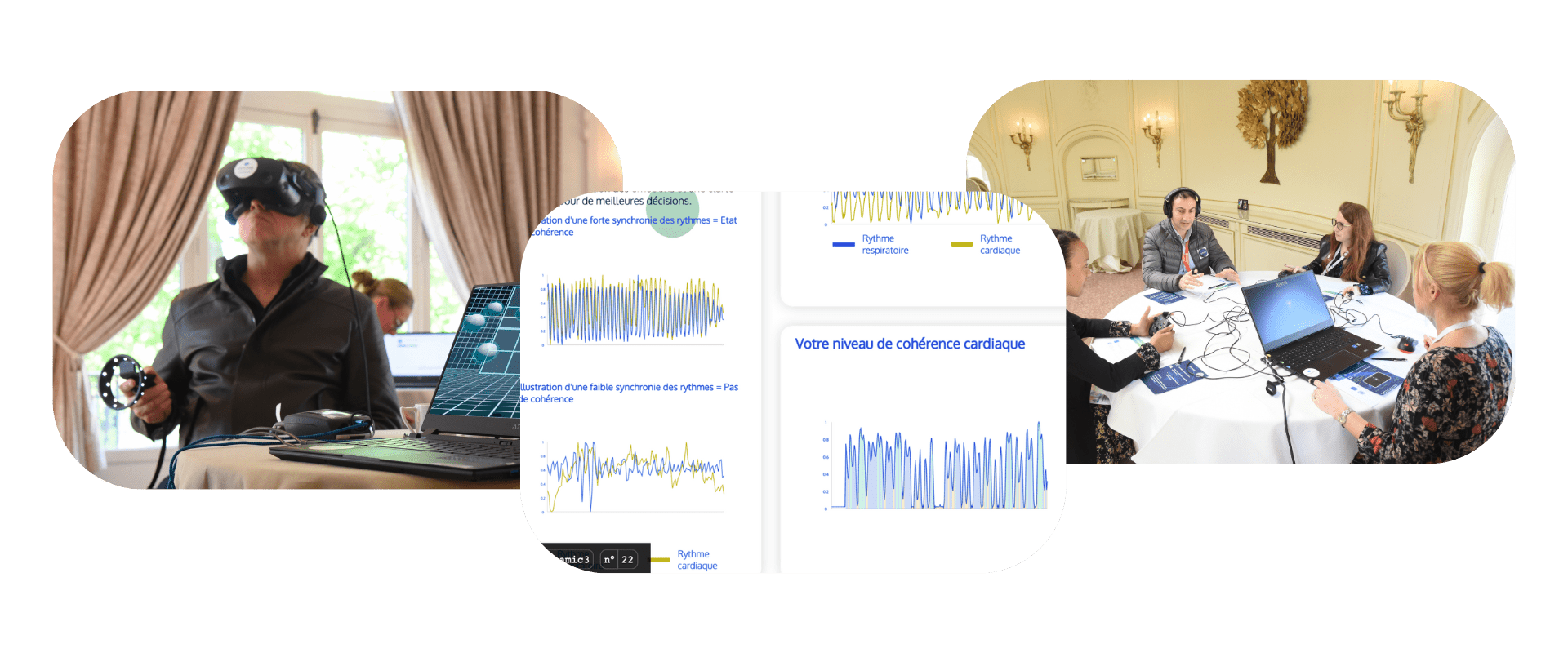

Come and test and train your awareness of yourself, your emotions and your cognition in the Omind neurotechnologies programs.

BONUS: "ETHICAL" AND "WISE" DECISION-MAKING

A fine example comes from neurobiologist Francisco Varela⁸ who, in his book What knowledge for what ethics? explains that the right level for making “wise” decisions would lie at a point of balance between the RATIONAL AND REFLECTIVE APPROACH (system 2) and AUTOMATIC, INTUITIVE AND BIASED DECISION-MAKING (system 1).

This equilibrium point would be slightly shifted towards system 1, which would allow decisions to be made quickly without too much energy, but would not be too biased.

Varela gives the example of a chess player who plays without being “conscious” of all the mechanisms involved in identifying the best move to make. But after playing, he is able to explain rationally why he made that particular move.